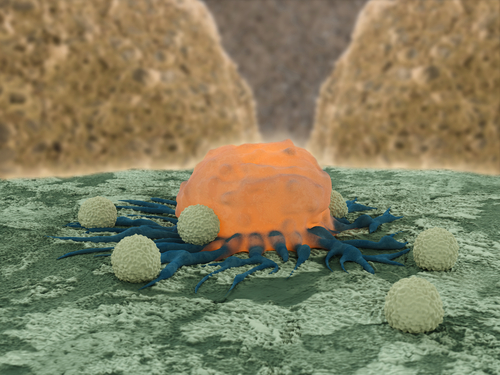

A new study performed in mice with breast and melanoma cancers reports that highly focused radiation, combined with a new immune-enhancing drug, helps the mice’s immune system to fight cancer.

A new study performed in mice with breast and melanoma cancers reports that highly focused radiation, combined with a new immune-enhancing drug, helps the mice’s immune system to fight cancer.

The study was presented at the American Society of Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) in San Francisco on September 15 by Andrew Sharabi, M.D., Ph.D., a resident in the Department of Radiation Oncology and Molecular Radiation Science at Johns Hopkins.

Recently, the FDA approved a new class of anticancer drugs, known as “checkpoint inhibitors,” which interfere with tumors’ capacity to impair its recognition by the immune system.

In this study, the team of researchers used mice with implants of melanoma and breast cancer cells on both their flanks that were treated with a checkpoint inhibitor during the whole period of the experiment. Mice were submitted to stereotactic image-guided radiation therapy targeting both flanks, but one flank was shielded and thus protected from radiation. The co-treatment radiation-checkpoint inhibitor led to a six-fold reduction of the tumor size, when compared with each therapy alone. Additionally, anti-tumor antibodies’ production and memory T-cells were also increased lymph nodes near the tumor with the combined therapy.

[adrotate group=”1″]

Sharabi noted, “The immune system has powerful brakes, and removing those brakes with checkpoint inhibitors may be a key to unleashing the full potential of the immune system against cancer. Adding radiation therapy to this mix may provide an additional boost by increasing tumor cell death and releasing targets for the immune system. We found that focused radiation therapy, once thought to suppress the immune system, actually increases specific, antitumor responses from the immune system,”

Charles Drake, M.D., Ph.D., associate professor of oncology and medical oncologist at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and the Kimmel Cancer Center, commented, “The increased immune cell division in lymph nodes suggests that radiating the tumor seems to activate immune cells in the surrounding lymph nodes, not just the tumor.”

Sharabi and colleagues showed the immune-memory of T-cells generated with the combined therapy by transferring cells from treated mice into normal mice, later injected with new tumors. As Sharabi noted, “The transferred immune cells inhibited growth of the tumors, suggesting that the immune cells can travel throughout the body and attack sites outside of the radiation field. Radiation causes damage to cancer cells, and the cells produce molecules called chemokines that can help to recruit an immune response.”

The researchers are now determining the optimal radiation, dosage, and timing that will generate the most efficient immune response.